I’ve been waiting for this.

I’ve been waiting for this.

Tl;dr Synopsis

This story is about lives coming together and ripping apart, but it’s done in a calculated way that builds to a crescendo and…well, kind of ends on a crescendo.

We’re introduced to Pip Tyler, a young girl with a lot of student debt and daddy issues. Andreas Wolf is a German Julian Assange, except he’s super cute and less rapey. Well, publically. Privately, he’s a troubled narcissist with mommy issues. Pip and Andreas come together and rip apart.

Andreas falls wholeheartedly, frighteningly in love with a teenage girl, and that teenage girl can’t ever get over the terrible thing they did out of desperation. Their lives come together and rip apart.

Tom Aberant and Anabel Laird (a journalist and an artist/psychotic mess, respectively) meet in college. Like being electrocuted, they’re locked together by a seemingly unbreakable force, both being psychologically fried to a crisp, until the current abates long enough for their lives to rip apart.

There’s little Purity airtime given to Tom and Andreas’s relationship. Their lives come together and rip apart in a matter of days. Then again, much later—this time for only one day—there’s another coming together and ripping apart. But I think this relationship might be the most important one in the book.

There is a plot to this story, but (1) to tell it here would fill this post with spoilers, and this is not a book I want to spoil for you, and (2) I think that this ebb and flow of relationships and the nature of how people come together and tear apart is the real heart of the story.

Writing Style

Franzen writes with clarity and frankness. He is an extremely accessible writer, but that’s not what makes him remarkable. What’s really incredible is how he keeps it accessible without sacrificing intelligence. Sometimes his passages take on a “literary” or “psychological” affect in a way that seems stilted, but that’s really the only complaint I have about the writing style. It is wonderfully modern, page-turn-y, and easy to read, but it’s also full of inventive simile and heart-gripping insight. I feel like this is best exemplified by passages, so let me throw some at you.

Right on one of the first pages, Franzen tosses out an analogy that’s perfect. Pip understands that she can get away with nearly anything, as far as her mother is concerned, because “she was like a bank too big in her mother’s economy to fail.” Pip’s mother (who, by the way, reads the news “for the small daily pleasure of being appalled by the world”) is just one character that demonstrates Franzen’s fascination with mothers and children. I suspect he’d been reading a good amount of Freud during the creation of this book because ol’ Sigmund is everywhere in Purity. It’s worth an entire separate post. Anyway, Pip’s mother is like Andreas’s mother, which is to say they are inevitably creators of victims. It’s discussed in this passage (and close your eyes if you don’t like profanity):

An accident of brain development stacked the deck against children: the mother had two or three years to fuck with your head before your hippocampus began recording lasting memories…you couldn’t remember a single word of what you or she had said before your hippocampus kicked into gear.

This is what I mean about Franzen being easy to read but never lacking intelligence.

Characters

Franzen’s character niche is “people totally out of control.” If they’re torn or distressed or confused or flailing, Franzen is all about them. You know who he really doesn’t do? Healthy, sane people with a complete sense of self. Maybe that’s what he’s trying to get at. None of us are.

Commentary aside, Franzen’s characters are almost always conflicted and, consequently, readers are almost always sympathetic. We’re in the heads of all the characters, and it’s hard not to feel for them, even if they’re the self-absorbed borderline Andreas or the self-martyred basket case Anabel. How they struggle, every one.

These characters are complex, and Franzen goes the extra mile by showing us how they got there. They aren’t always likeable, but you feel like you really see them for who they are, and it’s hard not to be invested in them.

That being said, some of the characters are totally ridiculous. Anabel, for example, is so over the top that it’s hard to see her as real. But I’ll just say this: I am a very character-centric reader, and this small complaint did not stop me from loving every second of this book.

Highlights

Oh, it’s so hard to choose between the endless highlights.

- Any of the more innocent, pure-hearted interactions Andreas has with the only two women (no, neither his mother) he truly loves more than himself

- The passages that follow Leila on her interviews in Texas

- Andreas’s childhood, though the experience is not entirely pleasant

- Pip’s time in South America

Really, most of the book is a highlight. I have a hard time going through Tom’s narrative, just because it’s such a long time of waiting for him to escape. You always sense it coming and are frustrated when page after page go by without any action. I also found Andreas’s relationship with Annagret after pining after her for years to be immensely unsatisfying, including the description of why it couldn’t work.

Who Should Read this Book

Everyone. I would recommend the book to absolutely anyone.*

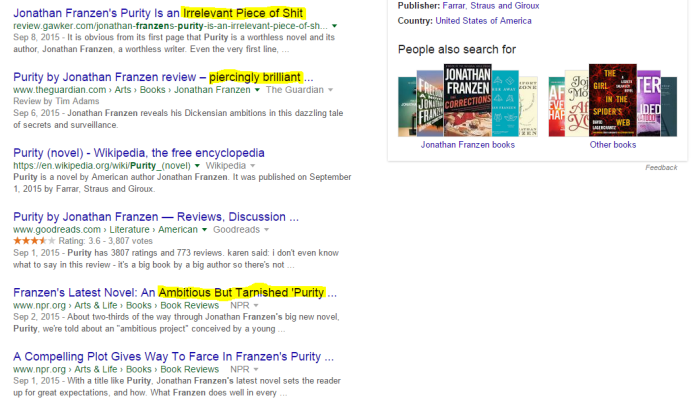

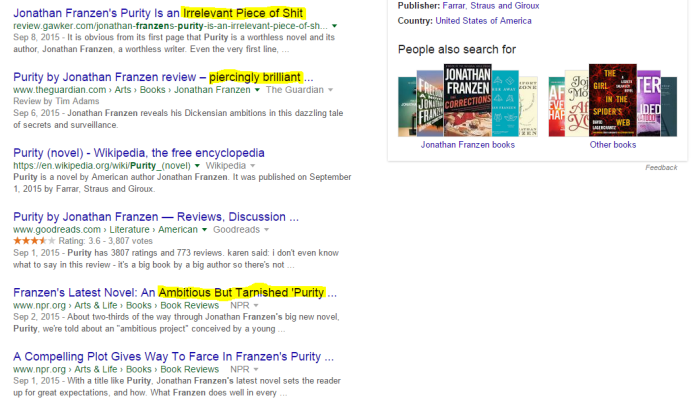

*Except maybe those in the literary community who are predisposed to vehemently hating the overdog without leaving room for nuance in their opinion. Or, you know what, maybe you’re not and still won’t like it. Google Purity and check out the polarized titles on the first page. No, you know what, let me do it for you.

Sycophants and haters. Everyone seems to be one or the other

For What It’s Worth (A.K.A. My Opinion)

Out of all the books I’ve read in the last month, this is the one that has haunted my dreams and made dreamscapes out my days. It’s like I’m lovesick. It’s taken me to another world, and it’s a world I haven’t been able to leave.

Let me be clear—Purity is not without its flaws (and I’m going to tackle the main flaw in a future post). Let me also be clear about this, though. Its flaws do nothing to stand in the way of how much I loved this book, loved the experience of reading the book, and love remembering the book.

And that’s really the difference between how I’ve felt about the other books I’ve been reading lately, even maybe in the last year. I’ve admired the craftsmanship of other books. I’ve been entertained and charmed and filled with respect. But I just flat out LOVE Purity. It hits something deep inside of me—the part that likes to get lost in stories and be swept up by the romance of a narrative completely separate from your own life, the part that likes to completely lose myself in a magnetic world that runs deep.

What Franzen is doing with Hamlet is pretty smack-you-in-the-face, if you’re looking for it. So I’m not going to go into too much detail. I’m just here let you know to look for it.

What Franzen is doing with Hamlet is pretty smack-you-in-the-face, if you’re looking for it. So I’m not going to go into too much detail. I’m just here let you know to look for it. I’ve been waiting for this.

I’ve been waiting for this.