So I read this collection of short stories in lieu of a 2012 winner. Yes, it is called St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, and yes there is a story about girls raised by wolves in there. It’s by Karen Russell, who was absurdly young when she assembled this. It has officially ruined my Pulitzer adventure. Why? Now my Kindle is loaded with every Karen Russell book in preparation for my upcoming read-a-cation in the Caribbean. Forget my Pulitzers. I found my new favorite author.

This book was outrageously creative–fantastically quirky–but so stirring. It is wild and other-worldly, feral and foamy and vivid. Karen Russell is my age, and she makes me feel both years younger and years older than her.

Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky talks about defamiliarization being the key to good literature. In essence, those authors who can take the everyday and mundane and show it in a fascinating new way are those who succeed at their craft. It’s funny–I think what makes Russell so great is the mirror image of what Shklovsky says. She creates these mysterious, completely foreign worlds that are startling and disorienting, but she adds such a human vulnerability to them that they have a heart-aching resonance. She takes the unfamiliar and re-familiarizes you with it.

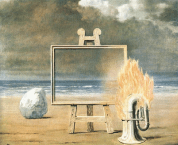

Have you ever seen an abstract piece of art that was not a recognizable reflection of the world we live in and yet pulled at something deep inside of you? Picasso’s Guernica is good for that. I know some people feel that way about Dali. Magritte does it for me…

Russell’s story reminds me of these images. They themselves are kind of whimsical and kooky, but there’s a real element of sadness or striving or connection in it all–a familiarity in all the creative rainbow swirls and shards of surrealism. Anyway, this book. For real.

Tl; dr Synopsis

There are a series of ten very imaginative short stories, taking you places you only dream of but solidifying the details that would be fuzzy in your sleep. There are manufactured blizzards for adult playtime. There are minotaur/human families. There are sleep disorder camps and learn-how-not-to-be-a-wolf-child camps. There are giant shells set up like a tourist trap, seaside version of Stonehenge. There are communications with the phosphorescent ghosts of fish. It is outrageous but not confusing, because there’s always a very familiar human element keeping you grounded. The stories aren’t just nonsense. They’re meaningful. And they’re over way too quickly. Perhaps my only complaint is that every story left me wanting more and almost feeling cheated.

Writing Style

Vivid! Fast moving. Never stilted. Full of colors and flashes and metaphor. Easy to follow. Almost as good as her stories, which is saying a lot.

Characters

Mostly children. It makes sense–these feel like children’s worlds, and readers wade through the intricacies of these strange new places in an appropriately hesitant, childlike way. What are the rules here? Russell writes very sympathetic children, or at least has a way of making us feel the way they feel.

Highlights

“From Children’s Reminiscences of the Western Migration” is so beautiful. This short story was the least cosmic, but it stuck with me the longest. It does a lot better of a job bringing the Oregon Trail to life than the game where all your friends drown in three feet of water. Oh, but the family patriarch in this story is a minotaur. It’s a gorgeous story about family and stubbornness and the slow, ugly, mob-like behavioral turns inherent in group dynamics.

Who Should Read This Book

Literally every person on the planet. Literally. It’s a fantastic time. It isn’t just that I appreciated the book and all its qualities. I had an absolute blast reading it.

Get on my Christmas list before December because everyone I know is getting this book.